I was introduced to the Shen-Hammer pulse system in 1996 after participating in several four-day Foundation Classes taught by his then student-teachers. Following these two workshops, I had already learnt and understood more about pulse diagnosis than in my four years of undergraduate study and two years of practice. Direct studies with Dr Hammer from 1997 onwards and the observation that my readings obtained from the pulse were remarkably similar to those of other students further nurtured my enthusiasm for the pulse.

Along with a handful of his other advanced students, a growing appetite for further knowledge lead me in 2000 to Dr Hammer’s Master of Pulse Diagnosis Program. Over a six-month period, we met for 4 days every month and saw 12 patients per workshop, feeling their pulses and working through their cases together. At the program’s conclusion, the ability of the students to take a pulse, interpret the findings and formulate a treatment plan was extremely refined and anecdotally, roughly analogous.

Further motivated by this observation and my increasing competency with the skill, an interest in academic inquiry inspired me to enter a Ph.D. research program. I was accepted to the University of Technology, Sydney (Australia) to examine the reliability of practitioners using this method clinically. All raw data for this research was collected at Dragon Rises College of Oriental Medicine in Gainesville, FL.

The study utilised a real-life design and engaged as testers Dr Hammer, myself and four of my contemporaries who had completed the Master of Pulse Diagnosis and displayed comparable skill (Laisha Canner, Brandt Stickley, Jamin Nichols and Hamilton Rotte).

Fifteen volunteer subjects whose pulses were unknown to the six testers were recruited. Two episodes of data collection were conducted 28 days apart as a practical test and retest. Four different pulse rates, eleven Large Segment pulse categories palpated bilaterally (First Impressions, Qi, Blood and Organ Depths, Waveforms among others) and twenty-nine Small Segment pulse positions (Principal and Complementary) palpated with one hand, were included in the study. For each subject during both phases of testing, these categories were assessed, reassessed and recorded on pulse forms by the testers according to the system methodology.

Intra rater reliability was measured by comparing individual tester results on day one with day two, while inter rater agreement and reliability were determined by comparing all testers across both days. Rates were analysed using ANOVA, while the remaining data employed Cohen’s kappa coefficient. Kappa values were interpreted according to previous clinical studies that incorporated a subjective tool to assist in clinical diagnosis. Cross-referencing percentage agreement with the appropriate kappa results rated the dependability of individual pulse qualities and positions.

The results supported the findings of earlier studies that suggested when a pulse diagnosis method is specifically defined, skilled testers can achieve acceptable levels of reliability. While rater reliability was found to be generally acceptable to good or above, intra-rater agreement was proved to be higher than inter-rater agreement. Large Segment categories or bilateral methods of palpation were identified as slightly more reliable than Small Segment categories, or those that assessed pulse positions using a single finger. Reliability according to pulse quality while again showing acceptable to good levels or above, identified Reduced Volume qualities as slightly less reliability than the remaining pulse quality classifications.

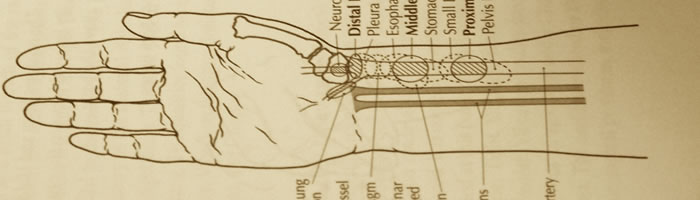

The research data identified areas within the pulse system where agreement levels among raters fell below acceptable standards. Unacceptable inter-rater reliability was clearly identified in the Diaphragm, Pleura, Esophagus, Distal Liver Engorged, and Heart Enlarged Complementary Positions. These results suggested inaccurate and confusing language in the descriptions for accessing these positions may have contributed to variance within the testers’ techniques.

These results were later evaluated by Dr Hammer and the group of testers during an Intensive Study weekend. The data accurately revealed that due to imprecise directions for accessing these positions, each of the testers had developed their own individual technique that differed from that of Dr Hammer’s. Following revision of these positions and updating instructions for palpation, the group of testers were able to modify their procedure for accessing these positions so that it more closely matched that of Dr Hammer and improved rater agreement.

Another outcome of this project was collaborating with the all the testers and some others skilled in the method to produce the Handbook of Contemporary Chinese Pulse Diagnosis, which I had the honour of co-editing with Dr Hammer. By sharing the expertise and insights of the group we aimed to provide a clinical resource that would support and educate practitioners in the field. (**Note Contemporary Chinese Pulse Diagnosis is now recognised as Shen-Hammer Pulse Diagnosis).

Through this research, we were able to identify areas that showed substandard levels of agreement and refine these for accuracy by implementing the indicated modifications. This is the first and only time to date, that a pulse diagnosis system has been tested by such rigorous methods, problems revealed, and with this information, specific actions taken for correction. The group of testers and their contemporary experts are the direct lineage holders and current teachers of the method. With an intent to keep the knowledge alive we work together to retain the ongoing integrity of the method, further validating the clinical use of Shen-Hammer Pulse Diagnosis now and into the future.